Building the Boat While Staying Afloat

Founding designers ship before they're ready, wear too many hats, and learn by breaking things. A conversation about the messy, uncertain reality.

There was a time when younger Laura wanted nothing to do with software. It seemed to always be in a perpetual state of change. Unstable. Unpredictable. Photography and concept art seemed like capturing a moment in time that wouldn’t have to “suffer” as much as UI would. I didn’t know a thing about building software back then, so I’ll go easy on my 20-YO-self because I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

These days, I thrive in uncertainty, exploring new ideas, and learning fast. The best school for this has been the role of Founding Designer at Beacon. Those who truly understand this role have lived through it. Like Tom Johnson.

This is why, when he recently announced he was leaving Basedash after 5 years of building a massive product as a solo designer, I knew I had to chat with him to reminisce about his early-stage startup experience and exchange learnings.

Why would any designer choose chaos? Not because they’re fearless. Because they wanted to know if they were actually good at this, outside the safety net.

When you don’t know what you’re building, experiments are your map

I left the safety of having a team, processes, and supporting roles to focus on my own thing, but I couldn’t fully own a product. Tom left a billion-dollar company where his work was “successful,” but he was never sure whether it was because of the company or his abilities. We both chose uncertainty over safety.

Early-stage is exciting because there’s an entire ocean to explore. Terrifying for the same reason. But how do you choose where to go when your compass isn’t even working yet? Time’s running out. Funding runway doesn’t last forever. And if you don’t pivot at the right time, someone else will beat you to the finish line.

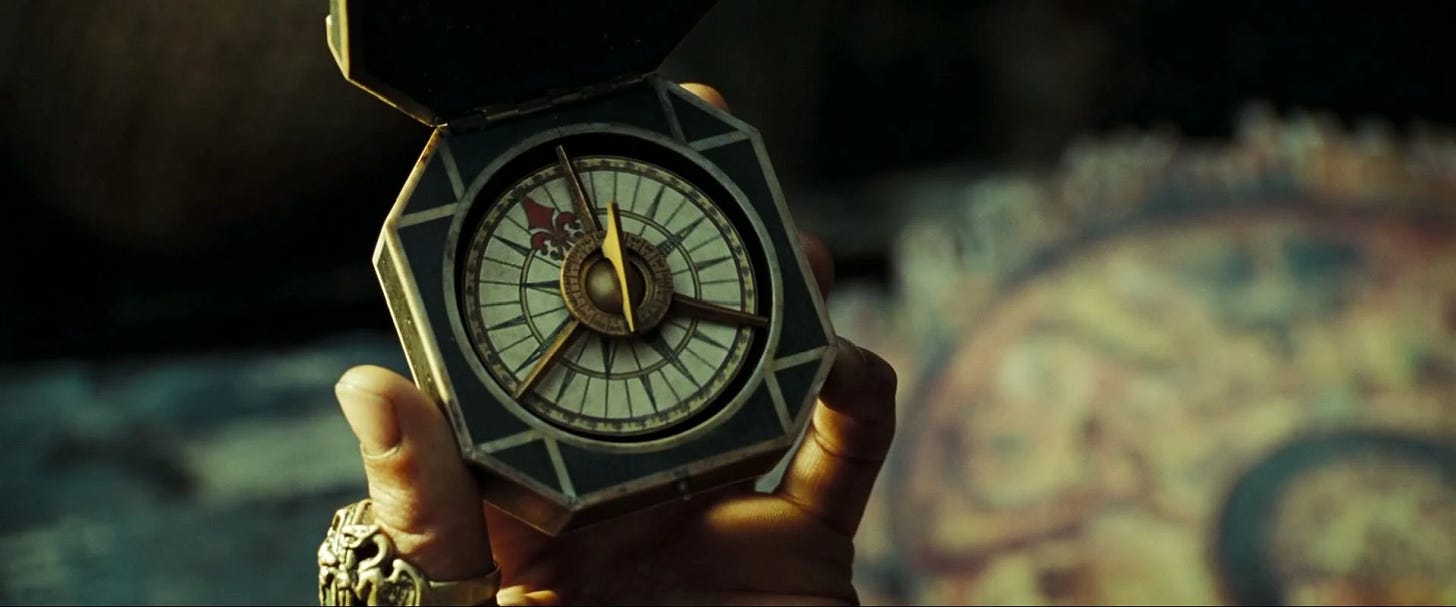

It feels like having Jack Sparrow’s compass guiding you. It’s not broken. It “points to the thing you want the most in this world.” But... how do you know what that thing is?

Like Jack Sparrow, you have to be a bit crazy to accept this compass and be willing to follow it. Much like a founding designer role.

One of my favorite parts of Tom’s long Twitter thread sharing 5 years’ worth of work was admitting that early on, you’re trying ANYTHING to get to PMF. We’re taking wild bets looking for signals, looking for the right user who needs your product. You can’t convince people to use it unless they truly need it.

So, how do you find the north on your compass? Ship. Ship like your life depends on it. Because, for the life of the business, it depends on it. And to ship the right bets, you have to step away from just looking at pixels to understand what needs to get built and why.

“In order for someone to be effective at design, they have to understand why a feature or product exists in the first place.”

— Tom Johnson

You achieve this understanding by wearing more hats than just design. Getting your hands dirty with 1000s of manual evals. Jumping on a sales call and realizing the person who’ll pay for your product isn’t the daily user. Making product decisions even if your role description doesn’t say you’re a PM.

This doesn’t happen in isolation, which is why influence is the best design tool. Your job isn’t designing features. Your job at a startup is about staying alive. Treading water until a boat floats by, and then figuring out how to build a boat that matches the boat that floats by.

You can’t plan your way to clarity; you prototype your way there

During our chat, Tom shared an interesting metaphor: “If you woke up from a coma and I showed you a picture of an automatic door and said, ‘Tell me how to open this,’ you’d be lost. No handle visible. But the trick is you just walk up to it. It just works. You never know until you use it.”

Most design looks intuitive in screenshots, but real intuition only emerges through use. Seems simple on paper, but getting to that intuition takes a lot of reps. How? Staying close to your users and building alongside them, by constantly testing out what’s intuitive to them. This ongoing access to your users is the fuel to keep iterating until “it just works.”

The traditional design approach would have you going through a lengthy process of planning and testing to develop intuition. When you’re on your own as a solo designer, the playbook shifts entirely. Instead of waiting for the perfect version of the feature to be launched and celebrated, you experiment. Internally, informally, saying “let’s ship it” and learning with the feature in production.

Building early is also about constantly generating prototype ideas beyond just clickable ones. You can run nimble experiments of things like tier packaging models. System prompts to reverse-engineer predictable outputs. Or setting up a table at a mall and getting feedback from people passing by in exchange for a $5 gift card. You’ll have to ask Tom about that story; it’s a good one.

You have to be comfortable letting go of prototypes and ideas. One-offs that serve the purpose of making the right decision and moving on.

Soleio calls this the hardest skill to develop:

“I think a lot of folks who buy the startup dream and want to work at startups want to get that like first song to be a hit, and they sometimes will just marry themselves to that first song, that first script, that first crystallized product idea, not recognizing that it may be a blind alley, it may be a short hill.”

— Soleio

Having the courage to show these prototypes to others to get honest feedback about how bad your app is over and over and over again is what builds your sensibility, your intuition. Every user struggle becomes a product improvement. Until you create a surprising effect on users. It just works.

Every experiment changes you. After enough of them, you’re operating at a completely different level. And it’s still you. A better version of you.

Trust the compound interest of learning + shipping. Most experiments teach you something, but don’t directly drive growth. You’re building before the payoff is visible.

What makes it hard is exactly what makes it worth it

Still nodding along? You’re in for an adventure.

Basedash was only 6 people. Beacon is 10. Both products look like they should require teams of 30+, yet they don’t. Heck, Tally built a profitable $3M ARR business with 4 full-time employees. How?

Lending Tom’s words:

“It takes incredible people with incredible talent to build a product like Basedash. Staying lean is what allowed us to stay focused and kept us all close to the work and our users.”

The first reaction of those who haven’t experienced the startup life before might include racing thoughts of whether or not you can pull it off. Wearing many more hats than you signed up for. Having more ideas than sprint points available. A lack of structure and processes to the point of feeling chaotic. I can keep going.

At the same time, the chaos that makes it uncertain is exactly what turns small teams into something else entirely. Wearing many hats develops product thinking better than any book. The constant influx of ideas becomes fuel for bold bets. The lack of formal structure gives you speed to pivot in days, not months.

Everyone is close to the work, close to users, close to decisions. The shared context is unmatched. Everything is your problem.

You’re not blocked by another team’s capacity or priorities in the org chart. You develop “full-stack product builder” skills. You build strong intuition through direct user contact, not research summaries.

Being a founding designer is learning in real-time, with real stakes.

This type of adventure is for those who see problems as opportunities, with an openness to learning while navigating uncertainty. The comfort with not knowing. And then, everything becomes your impact.

Parting thoughts

Not everyone should be a founding designer. But if you’re still reading, you might be one of them. The ones who left success to test if they were actually good. Who’d rather ship and learn than plan and hope. Those who see uncertainty as a creative constraint, not a paralyzing risk.

You’re not designing products. You’re discovering what the product wants to become. You’re not following a roadmap. You’re creating the map by walking.

Thanks for the inspiring chat and collaboration, Tom. Here’s to building in public and figuring it out as we go.

PS. How to spot a founding designer

Shortcuts

Tom's 5-year journey at Basedash, a walk down memory lane full of candid lessons

How To Win Friends & Influence Decisions, by Julie Zhuo, sharing practical examples on how to drive influence as a product builder

Don’t trust the (design) process, by Jenny Wen, encouraging us to embrace the messy process

From 2 to $3M ARR: How We Bootstrapped Tally With a Tiny Team, by Marie Martens, co-founder of the mighty team at Tally

That’s where curiosity led me this month. Your path will look different, because context always matters.

If this sparked something, let’s continue the conversation on Twitter. And if someone you know is navigating their own creative uncertainty, share this their way.

Keep exploring, Laura ✌️